PhD student Neil Hume reflects on a community forum held by the Binks Hub in Craigentinny Commity Centre in December 2021.

“Wrap up warm” we reminded invitees: we knew that even after one of those wonderfully blue and brisk winter days in the capital, with the darkness always comes the cold.

I’m Neil Hume, a second-year PhD student in social work at the University of Edinburgh. Alongside the social innovation charity People Know How, I am exploring ways to improve the support provided to those young people who struggle with their transition from primary to secondary school.

I’m thrilled to be part of this small but rapidly growing group of social researchers affiliated to the Binks Hubs. Being new to the world of participatory action research but committed to finding interesting and inclusive ways of working with people, I jumped at the chance to be involved with the first Binks Hub Community Forum in Craigentinny. Helping to plan and deliver this event alongside Autumn Roesch-Marsh and Jimmy Turner, two such experienced and enthusiastic practitioners was a lot of fun and a real privilege.

In this short blog, I reflect on some of my learning, focusing in particular on how warmth – both physical and emotional – played such an important role in making the session successful. For a flagship event designed to ignite local interest in the Binks Hub, the freezing weather, a breezy hall, and empty chairs ran the risk of pouring cold water on our morale and the mood of our guests; I did wonder to myself if this is what Steven Kemmis and Robert McTaggart (1992), those stalwarts of action research down under, meant when they recommended always starting small!

Having the brilliant Scran Van crew at the venue to provide hearty fare helped everybody feel heated and nourished. Rifting on Maslow’s humanist hierarchy, I’m not saying that tasty soup is a short cut to self-actualisation but getting the basics sorted is a step towards creating the conditions to let people do the more complicated cognitive stuff.

I think in the context of this event, running at tea-time on a Monday and knowing the folk coming could well be hungry and tired, it was also a caring and courteous act by the team towards our guests. Thinking about how I might organise and run workshops as part of my research, seeing to these essentials, ensuring people attending feel comfortable and valued, will now be front and centre in my planning.

When Kemmis and McTaggart (1981) talk about action researchers scoping their ’field of action’ to choose where the battle (not the whole war) should be fought (p. 2), I was always uncomfortable with such militaristic language. My misgivings that our visit could feel like an incursion weren’t abated by the fact our venue for the event was an actual castle (complete with keep, towers, and friendly ghost).

It was telling for me that one key theme from attendees’ questions was about our commitment to the cause: one person queried exactly how long the Binks Hub would be working with them, another shared that how promises in the past from other organisations had not been fulfilled.

Maybe ordinary people are right to be wary of researcher’s motives and morals; a major flaw of much conventional research into issues such as social disadvantage is that it inevitably involves outsiders coming into an area, getting their data, making findings, and then leaving again, with little or no tangible benefit to the community (Hall, 2005). Underpinning such top-down approaches are all sorts of elitist beliefs and assumptions about who has expertise and who should be in control of the research.

It was vital from the outset that our involvement was not the ‘same old story’: an agenda and way of doing research that was not imposed or felt remote, but collaborative and clearly relevant. Autumn and Jimmy shared with the audience that though they had experience and skills in doing this type of research which they wanted to share, it was the people who lived and worked in this neighbourhood who knew which issues mattered and would be key to bringing about change. They were up front about both the opportunities the Binks Hub might bring locally, but also it’s limitations in terms of tackling some of the more deep-seated structural issues such as high unemployment or inequality.

I was learning first-hand that one of the trickiest tensions to manage within action research is finding ways to inspire people about the transformative potential of this approach, to bring people who might be sceptical or uncertain with you, whilst all the time managing expectations and not giving false hope.

When you are seeking to identify problems – an important goal in the early stages of any action research project (McNiff, 2014) – there is a risk that things can take a negative turn. In an exercise we ran in which attendees shared their views and opinions on life in Craigentinny, with Autumn and I recording key words and comments on a flipchart, there were far more adversities than strengths.

Of course, this could be an entirely accurate account of how things currently are. Still, reflecting on the material afterwards, the team wondered whether through our prompts and responses we unintentionally somehow implied we wanted to hear more of this type of information. It could also be that as our participants were local leaders, working as a councillor, managing a community centre and running a charity, they were more accustomed to speaking the language of local troubles and unmet needs.

That’s not to say we or our partners were necessarily blinkered or biased; but thinking critically about how our narratives about areas affected by disadvantage can so quickly slip into a deficit model, I was reminded of Matthew Desmond’s observation from his own fieldwork that “a community that saw so clearly its own pain had a difficult time sensing its own potential” (2016: p.182).

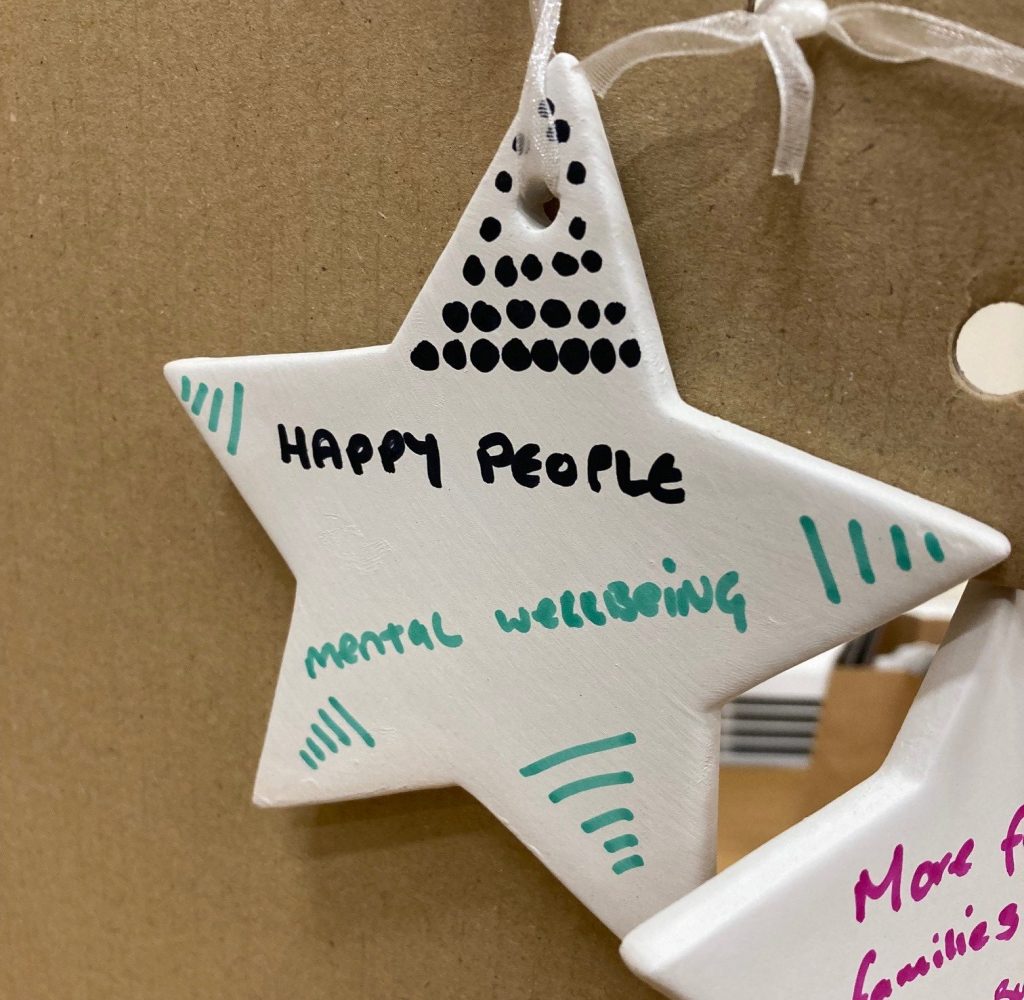

In our final exercise, we purposefully looked towards the future: everybody was invited to think of their two wishes for Craigentinny, writing them down on ceramic stars we’d bought to adorn a dainty and eco-friendly cardboard tree.

This fun, festive-themed activity helped this first session end on an upbeat and more hopeful note. Looking back at my first experience of being involved in an action research project, and considering the challenging circumstances everybody faced, what has stayed with me is this sensation of warming up: within ourselves, against the elements, and towards each other as researchers and participants meeting and working together for the first time.

We warmed up to trying out novel and creative methods, and to a vision of the Craigentinny community that is proud and resourceful with incredible potential.

References

Desmond , M., Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City (London: Allen Lane, 2016)

Hall, B. ‘Breaking the monopoly of knowledge: research methods, participation and development’ in R. Tandon (ed.), Participatory Research: Revisiting the Roots (New Dehli: Mosaic Books, 2005)

Kemmis, S. and McTaggart, R. (eds), The Action Research Planner (1st Edition) (Geelong, Victoria: Deaking University Press, 1988)

Kemmis, S. and McTaggart, R. (eds), The Action Research Planner (3rd Edition) (Geelong, Victoria: Deaking University Press, 1988)

McNiff, J., Writing and Doing Action Research (London: Sage, 2014)