On Wednesday 1st October 2025, the Binks Hub extended an invitation to policymakers, practitioners, and researchers interested in re-imagining fresh futures by posing the question: Can (and should…) we weave planetary health thinking more deeply into the fabric of our public health systems?

Planetary health as public policy emerged almost a decade ago with the aim of weaving explicit acknowledgement that human health is deeply dependent on the health of the planet, within the context of Earth’s environmental boundaries. The Binks Hub views the rise of planetary health policy as symbolic of a broader desire to unearth alternative stories of the world that our systems and structures can build new principles around.

This interdiscplinary brainstorm session, located at Edinburgh Futures Institute, was facilitated by Dr Scott Davis who leads the creative-relational natural assets workstream within the Binks Hub’s REALITIES project.

The seminar hosted presentations and facilitated creative activities that sought to nurture new ways of acting and thinking. We invited attendees to question their own anthropocentric understandings of the world, to de-centre human subjectivity, and to challenge the sometimes reductionist ways we design research and policy in the places and communities we work alongside.

Understandably, this longer-term work of interrogating present ways of thinking, being and knowing to develop alternative re-imaginaries that reflect planetary health principles can be a complex, gradual and emotionally demanding journey to embark upon.

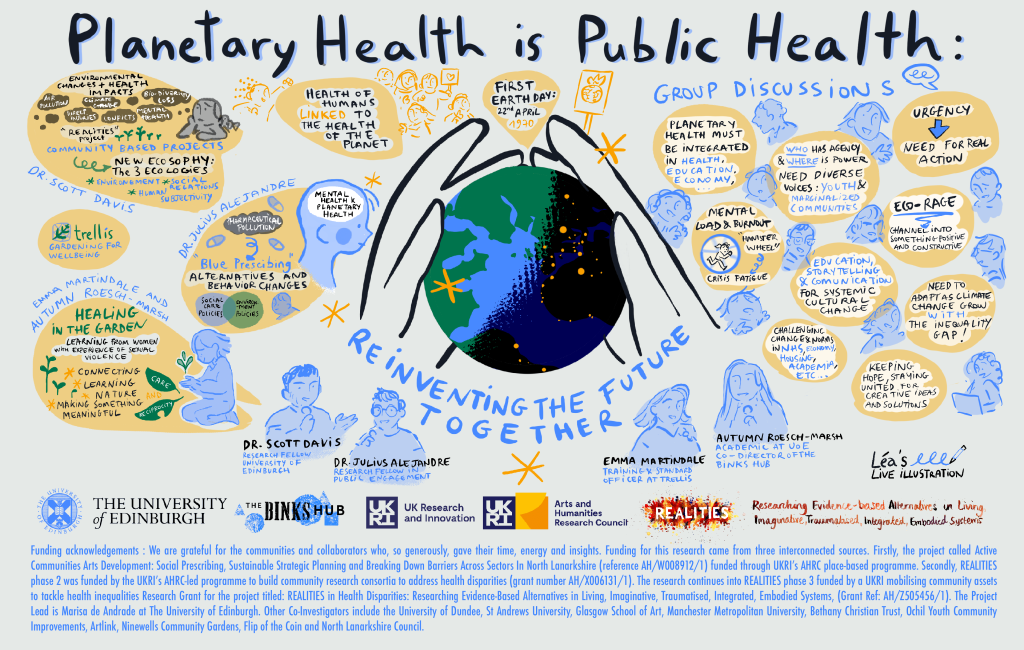

The morning session included three presentations (see below for detailed summaries). Dr Scott Davis introduced the concept of planetary health, describing its history and its rise as an influential policy discourse, which he now applies in his own work. Dr Julze Alejandre presented exceptional insights into green and blue prescribing frameworks currently delivered across Scotland and Dr Autumn Roesch-Marsh and Emma Martindale from Trellis Scotland offered a thought-provoking and moving case study of reciprocity, care and healing within a community garden from women with experience of sexual violence.

The afternoon session consisted of various group discussions, prompted by three thought-provoking questions, during which attendees were asked to reflect, write/draw, and share their insights and experiences together in relation to the prompts. Two playful thought experiments followed, entitled When the Earth stops spinning and The House of Modernity, adapted and inspired by Dr Vanessa Machado de Oliveira’s book Hospicing modernity: Facing Humanity’s Wrongs and the Implications for Social Activism. These experiments helped to question our planet’s impermanence and reflect upon the materials we use and the assumptions we hold in our day-to-day lives.

The seminar concluded by reflecting on the fresh insights and new connections created that day and asking whether something more should come of this seminar, or whether it should be left as a moment in time.

We thank those who attended the seminar, both familiar and unfamiliar with the concept of planetary health, who shared their thoughts and experiences that could be taken forward into future public health research, policymaking, and practice, creating new connections and relationships throughout the day. Scott and the Binks Hub team would also like to thank Léa Pietrzyk, our visual minute-taking illustrator.

We believe the seminar was a great success and we look forward to hosting further planetary health events in the future.

Presentation Summaries

by Erika Bunjevac, Hannah Connuck and Jingru 'Cecelia' Zheng

Introduction to planetary health

Dr Scott Davis from the Binks Hub provided an introductory framework for the presenters, elegantly detailing the history of planetary health as a concept and its increasing weight in academic literature and social policy.

Planetary health is defined in alignment with the UKRI and Rockefeller-Lancet Commission, as ‘a focus on the health impacts (in humans, animals, and plants) of human-caused disruptions of Earth’s natural systems and the development and evaluation of potential actions to create positive feedback loops between a healthy environment and a healthy society.’

In particular, environmental changes such as air and chemical pollution, biodiversity loss, climate change and marine degradation impact human health through means like direct injury, displacement, conflict, or mental, nutritional and reproductive ill-health.

Prior discussion of data-driven policy was balanced with a breakthrough cultural and sociological perspective, guiding the session into the ongoing ‘REALITIES in Health Disparities’ project, supported by UKRI. The project connects with five community hubs across Scotland – Edinburgh, North Lanarkshire, Clackmannanshire, Dundee and Easter Ross – to co-produce knowledge in tandem with local practitioners.

Methods include building a community garden at Ninewells Hospital and a/r/tography, an arts-based process of inquiry. The study aims to “critically investigate the potential of creative praxis to strengthen the relationship between communities and their local environments” and spur further critical examination of the extent and limitations of relationality and a humanistic approach in planetary health action.

A standout point from this talk is the notion that planetary health is not a novel concept. Its rising popularity starting in the 1970s appeals to a desire to re-establish pre-industrial natural connection. Indigenous scholarly works and knowledge systems continue to provide valuable guidance in this regard.

Blue-Green Prescribing

Dr Julze Alejandre’s presentation of “Beyond Pills: Blue-Green Prescribing for Population and Planetary Health” summarised a variety of studies that explored prescribing nature-based activities to improve mental health treatment plans that also benefit the environment. Supplementing or replacing medications with blue-green activity prescriptions reduces the amount of medication that later enters the environment through wastewater and harms aquatic life.

The objective is to build a patient-centred approach to mental healthcare through nature-based and eco-directed prescribing. Nature-based social prescribing of activities like surfing, hiking, and swimming that connects people with guided activity in green and blue spaces to support mood, social connection and adherence. and eco-directed prescribing of lower effective doses and less toxic medications.

Scientists and other stakeholders developed several implementation strategies that lead to four main outcomes: 1) accessible and equitable blue space activities for mental health, 2) environmental considerations in quality mental healthcare prescription, 3) collaboration for evidence-based blue-green prescribing, and 4) stakeholder investment for mental health.

All of the strategies and outcomes serve the overarching goal of improved mental health and wellbeing of people in Scotland and reduced pharmaceutical pollution in the water environment. Building up accessibility to blue-green prescribing for patients and integrating the practice into existing structures and policies that advise prescribers, this framework enables healthcare workers to “[focus] on public health strategies for human prosperity”, as Dr Alejandre so eloquently put it.

Blue-Green prescribing is acceptable, appropriate, and feasible in Scotland, although barriers still limit the ability and want for stakeholders to take up this practice. A persistent barrier is the lack of awareness and access to training among healthcare providers which the project addressed by developing toolkits to educate and assist healthcare providers.

Effective programmes would focus on patient enrolment, engagement, and adherence to treatment plans with an emphasis on clear communication and long-term sustainability. Policymakers are prepared to support blue-green prescribing but see the need to resolve barriers limiting access for healthcare workers and patients. Services should prioritise access to blue and green activities, integrate environmental sustainability, strengthen cross sector collaboration and audit outcomes for fairness.

This programme places mental healthcare within a planetary health frame and offers a realistic route to better personal health outcomes and a smaller pharmaceutical footprint.

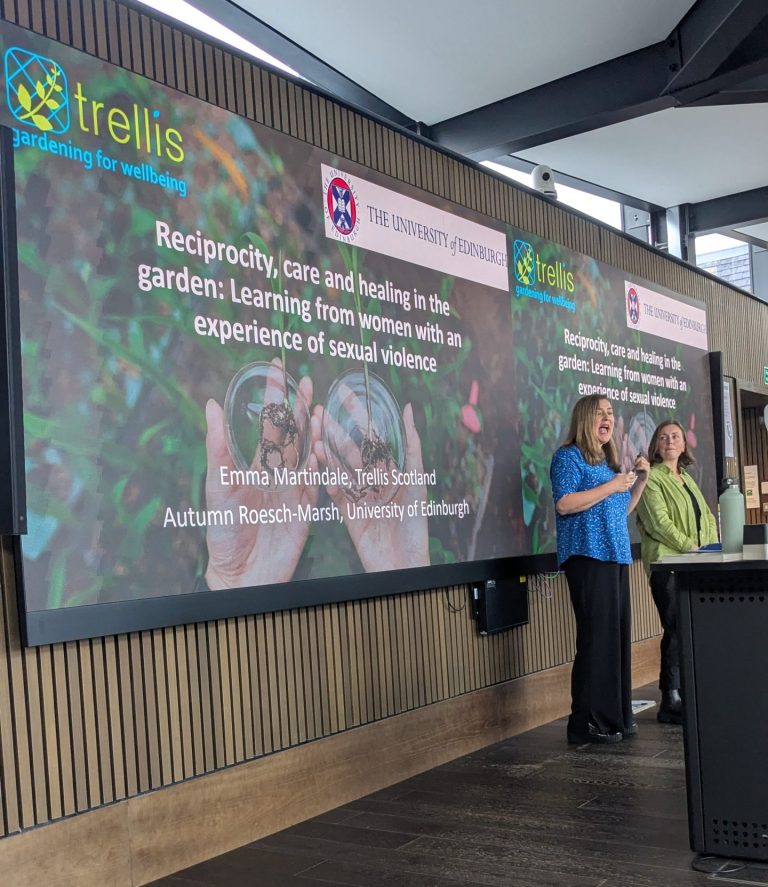

Reciprocity, care and healing in the garden: Learning from women with an experience of sexual violence

With an introduction by Dr Autumn Roesch-Marsh from the University of Edinburgh, Emma Martindale, a horticultural therapy practitioner, presented their work with Trellis Scotland titled “Reciprocity, care and healing in the garden: Learning from women with an experience of sexual violence”. At least 36% of women in Scotland experience sexual assault at some point in their life, and there are lasting physical, psychological, and social effects from this trauma. Although all types of trauma are different and unique to every individual, there are similarities that suggest the ability to extend the techniques used in this study to other types of trauma informed practice.

From the start, Trellis found a natural fit for the project at Birkill House, a facility designed to improve mental health and wellbeing in the Scottish Borders through crafting, connecting with nature, and collaborating with others. Over the course of 18 months, the women participating in the project grew a natural dye garden from the early planning stages through the processing and use of the garden’s products in various crafts.

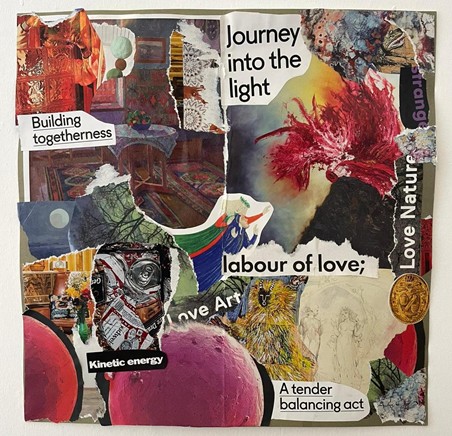

Research collaborators acted as facilitators, documenting their observations and reflections throughout the programme and encouraging participants to do the same, through journaling, questionnaires, and discussion. Through this process, a series of testimonials painted a picture of these women’s lives and how their involvement with the natural dye garden impacted them. The most impactful facets of the programme were connecting with other people, connecting with nature, and making something meaningful.

Connecting with other women in a safe environment was extremely valuable to them. Many of these friendships extended beyond the weekly gatherings and beyond the 18 months of the programme, reducing feelings of loneliness and isolation when previously many of the participants found themselves socially withdrawn.

Facilitators leveraged social and therapeutic horticulture and green prescribing to use nature-connected activities as a treatment for mental wellbeing. Whether they were avid gardeners in the past or had no experience at all, the women considered connecting with nature to be one of the most significant benefits of the programme. Spending time in the garden fostered their love of nature and got their hands dirty. The process of meaningful production of art from the plants in the dye garden inspired pride, accomplishment, fulfilment, and confidence.

Reciprocity is an uncommon tool in social work, but this study emphasises the importance of acknowledging the value of what a person has to give. Often, social work flows one direction from a social worker to a person receiving their help, whereas this project focused on returning agency and empowering participants to administer and reflect on their own care. The care that was put into this previously neglected garden over two growing seasons exemplified this two-fold benefit to the natural environment and to the women tending it. Viewing social work as a partnership between individuals and a collaborative body of work (in this case a garden) empowers individuals and communities to trust and collaborate with each other.

Cover image: Milena Trifonova

Photos credit: Leah Soweid